It’s time to stop delegating creative thought.

Last week, while waiting for a train to take me to an event I was already 15 minutes late for, I was subjected to the MTA’s compilation of short-form video content. Usually, these 10-30 second videos are messy-looking “food hacks” from Russian content farms or glossy TikToks about secondhand shopping destinations. This time, I noticed a new addition titled: “How to Wear Butter Yellow”. “Start with accessories”, the video advised, as the woman onscreen held up a pale yellow purse. Although this video is designed to be nothing but frivolous background entertainment for bored commuters, it also encapsulates the delegation of everyday creative thought we’ve become accustomed to in the past several years.

It can sometimes feel like every movie is a sequel or reboot, every red carpet look is a head-to-toe runway reference, and every content creator is replicating the same algorithm-approved formula to go viral. We hear the same sound bites in the same cadence, are constantly reminded of our nostalgia, and are force-fed existing IP until it fatigues us. I mostly attribute this phenomenon to one word: optimization. In the late-stage information age, there’s an over-reliance on data to show us what works and what doesn’t. There’s little room for experimentation. Deviating from statistically proven success is a risk that can be easily avoided if you follow these ten easy steps! We become inundated with a sameness that only reinforces itself. We reference references. Imitations of imitations proliferate, distancing us even further from the original.

We’re several steps away from originality now. West Village cool girls swish by in black gauchos, a nod to what they might have worn in elementary school in 2002 with foam flip-flops. Those gauchos were a recycling of a 1970s trend that in turn came from South American cowboys in the Pampas. Fashion is cyclical and constantly reinventing itself, but the noticeable difference now is that there is little deviation from the source of inspiration other than cost-cutting measures. Gauchos went from utilitarian cotton, to brightly-colored flannel, to spandex, to spandex (but cheaper). Ten to fifteen years from now, when searching for “vintage y2k clothes” on ebay, there will be far more listings of fast-fashion dupes of sparkly butterfly crop tops and ruffled denim skirts than there ever were of the original 2000s items.

In June 2024’s edition of British Vogue, writer Julia Hobbs suggested that the general public may now enjoy being less individual in their style. Thanks to TikTok, there has been an explosion of short-lived microtrends that are impossible to keep up with. “You can only get so far ahead of the herd before the herd catches up, then overwhelms you, and therefore it’s easier to succumb to the tide”. If anything, that algorithm fatigue she describes sounds like an endorsement to divorce oneself from it completely. Even trying to be swallowed up by what’s en vogue is futile– trend cycles are shorter and shorter, and refreshing your wardrobe each time a new look hits the scene is untenable and exhausting. It’s also a lifestyle only made possible due to fast fashion, which can stay on top of what’s hot on social media without worrying about production time being stalled by ethical working conditions or quality manufacturing.

“When you make a thing, a thing that is new, it is so complicated making it that it is bound to be ugly. But those that make it after you, they don’t have to worry about making it. And they can make it pretty, and so everybody can like it when others make it after you.”

– Pablo Picasso (as quoted by Gertrude Stein)

I’m not against all fashion guides. It’s good to share knowledge, particularly within marginalized communities where information is not widely available or accessible. Copying others is also how we learn. In my early internet days, I learned from bloggers like Susiebubble, Keiko Lynn, and The Sartorialist. I looked at collages on Polyvore made by teen girls dreaming up their first date outfit with Justin Bieber. My issue is that many people create guides as if there is an agreed-upon standard we can all reference about what is good and what is bad, and many others take this information at face value.

Drawing inspiration from our surroundings and processing new knowledge through our own lens is something that happens constantly, often without our knowledge, and is an integral part of creation. I take issue with fashion guides because, counterintuitively, they actually eliminate that step of the process. A shocking amount of figuring out what looks “good” is completely subconscious, and an even higher amount is subjective. I always find trying to reverse-engineer my thought process about why X looks better with Y than Z a bit confusing, if not frustrating, because there are so many factors influencing my thought process that I can’t identify and explain them all. The best way to figure out your style is not to read every guide. The best way is to take thirty minutes and play around in your closet or go to a store and try on a bunch of things. Better yet, learn from getting dressed every day.

Optimizing fashion assumes that the wearer’s only concern is the end product, the outfit as it is perceived. You don’t have to spend time searching for something when there’s a link to shop in bio. You don’t need to figure out what would look good with your new trousers when there’s a hundred photos Pinterest’s AI-driven search algorithm can serve you. You don’t need to think about color combinations or hairstyles or even how to pose in the photo you’ll take for your Instagram feed. All that thought has been delegated.

A recent study at MIT suggests that even over the course of a few months, ChatGPT use has significant negative effects on critical thinking. By using an EEG to monitor brain activity while responding to SAT essay prompts, researchers noted that ChatGPT users “consistently underperformed at neural, linguistic, and behavioral levels”. The ChatGPT users put in less effort with each subsequent response, were not able to rewrite essays they had written previously when prompted, and showed weaker alpha and theta brain waves compared to writers who did not use AI. Our ability to form creative thought is a skill that atrophies when we avoid exercising it– ask any former art student who ended up stuck behind a desk after graduation. Some people claim that this delegation frees up their time to pursue other interests. For one, these thoughts can become nearly instantaneous when the muscles making them are well-trained, and for another, the people usually expressing this interest are usually not using their extra time for much at all. Human life is about more than creating the most productive self.

There’s also the question: cui bono? There are incentives to making it appear that there is an empirically proven way to dress well, and only one person has cracked the code (but, of course, they’re willing to share). It drives clicks, views, and follows, and in some cases, it’s just a good old-fashioned grift.

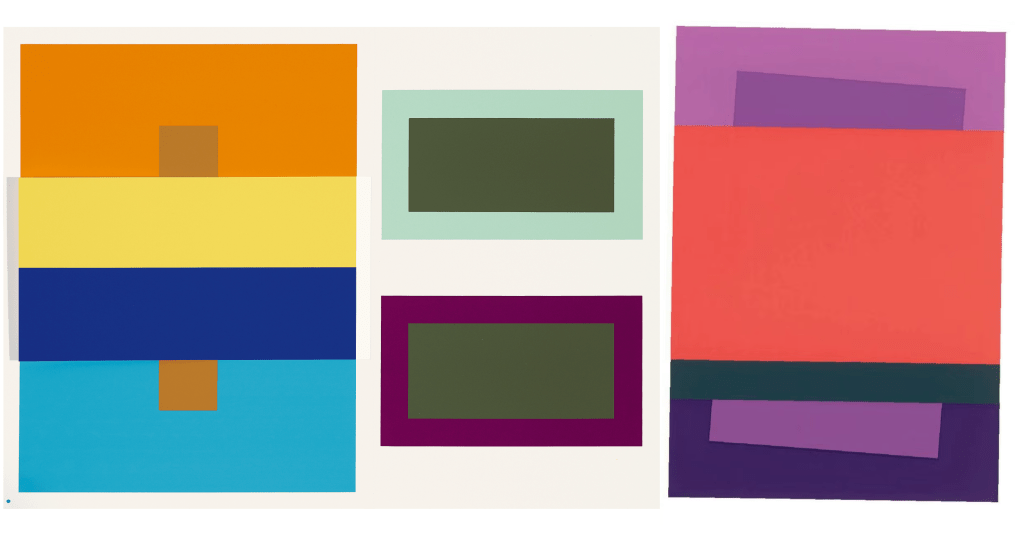

“Color theory” guides are an interesting case study. Or, at least, a hyperspecific version of color theory that often includes a woman in a salon chair being shown swatches of fabric next to her cheek, or a tiktok filter with a face cutout like a carnival standee. Viral videos are titled things like “You’re not ugly, you’re just wearing the wrong colors” or “personal color analysis has changed my life and i hope it does for you too 😝”. These videos intend to highlight the importance of matching clothes, makeup, jewelry, etc., to one’s skin tone. The most popular form of categorization sorts people into four easy categories: spring, summer, autumn, and winter. Spring colors are bright with warm undertones, summer colors are muted, with lower color intensity, autumn is earthy and vibrant, and winter is deep and cool. Of course, to account for any fuzziness, there are also “universal colors” that should suit anyone. Even so, one look at the top comments on any of these videos should show just how little consensus there actually is on what suits the original poster.

If you were to look up “seasonal color analysis”, there would be a plethora of guides instructing you on how to find your type. Look at the veins on your wrist! Do you look better in gold or silver? What color are your eyes? Try going out in the sun! Although the majority of these handbooks are surely well-intentioned, it is once again an attempt at approaching fashion as empirical and qualitative. Colors indeed change their optical appearance based on what other colors are near them (like your hair and skin), but it doesn’t stop there. They change when appearing in patterns or varied quantities, when presented in different lighting, when seen through a camera, when seen by different viewers, and so many other instances. Attempting to prove that one color palette solution is superior for all circumstances is futile. Sometimes we need this kind of useless crutch to get over a mental hurdle preventing us from moving forward. Having a set color palette to choose from narrows down the impossibly wide world of fashion into a smaller spectrum that’s more manageable. But it shouldn’t be treated as dogma, and it shouldn’t be restrictive.

We’re surrounded by constant visual stimuli, and yet we all go back to the same 50 photos on our moodboards. Next time you want to experiment with something new (butter yellow, anyone?), eschew the internet. How is butter yellow used in food packaging at the grocery store? Or book covers at McNally Jackson? Look back through your camera roll of selfies to see clothing combinations you loved, or ones that didn’t work so well. Spend time playing in the closet and in the dressing room. Draw from the people around you and the strangers on the street. Look at Sargent paintings and Dario Argento movies and graphic design wheatpasted to the wall. The result you get will be yours and yours alone, but you may find that the seeking is enjoyable in itself.

Leave a comment